Rufus Putnam is considered the founder of Marietta, Ohio. He had a distinguished Revolutionary War record. His specialty was fortifications. In early March, 1776, George Washington was planning a campaign to force the British army out of Boston. Rather than a risky frontal assault, he and his staff decided upon secretly fortifying Dorchester Heights with heavy artillery. Control of those hills with would give Americans effective command of the city. Rufus Putnam was a key player in this early Revolutionary War action.

The armaments1 brought from Fort Ticonderoga were ready. Bombardments at other locations were planned to distract the British. Nearly 5,000 recently recruited and enthusiastic patriots were eager for action. There was only one problem: the cold. The ground was too frozen to build trenches, earthen walls, and timber structures needed to defend the positions once occupied.

One night Putnam, then serving as an engineer building fortifications, was invited to dine at headquarters. George Washington asked him to stay afterward. He spoke passionately about the importance of fortifying Dorchester Heights. He was anxious to start the campaign but frustrated that frozen ground was holding things up. Rufus recalled, “the General (Washington) directed me to consider the subject and if I could think of any way in which it could be done, to make report to him immediately”

Rufus Putnam was the right person for this situation. He had mastered several trades by the time he was twenty years old. He was curious and relentless in solving problems. He started back to his own quarters, his mind racing. A cold wind whipped around him, an annoying reminder of the urgent situation. He passed the quarters of General Heath. Putnam recalls vividly that “(divine) providence” prompted him to stop and visit Heath. He had no reason to do so. Heath welcomed him. Putnam noticed a large book on military fortifications sitting on a table. He coaxed a reluctant Heath into lending it to him.

The next day he perused the book. His eyes fell upon an illustration of a chandelier. It was not the light fixture of today. “What is that?, he wondered, “….it is something I never heard of before.” The next page explained how it was used. That would work! It was a low tech solution: tightly wrapped bundles of sticks (fascines) were placed in wooden frames (chandeliers). No digging required. It would stop small arms fire and grape shot. They could be quickly assembled, transported, and mounted on the hill. He consulted with his staff, then reported to Washington who approved it. Immediately they started building the structures.

At 7:00 pm on March 4, 1776, 4,000 Continental Army troops stealthily hauled armaments, the frames, and bundled sticks up the hill in hundreds of horse and oxen carts. Thunderous cannon fire from other locations distracted the British - and terrified Boston residents. A full moon helped the patriots; a light fog hindered British visibility. Bales of hay piled along the route stifled noise. By 4 a.m., the operation was complete.

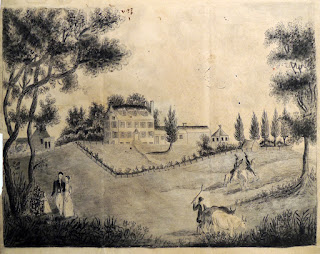

Image of American forces on Dorchester Heights, standing behind Putnam’s chandelier frames

and bundled sticks

At daylight, British sentries were shocked to see the plainly visible artillery placements. British General Howe reportedly said: “The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army would have done in a month.” Days later, the British evacuated Boston and never returned. It was a major victory for the patriots, enabled by the quick thinking Rufus Putnam. Washington had tried to recruit him as Chief Engineer, though Putnam declined, believing he lacked the qualifications for the job. A decade later, Rufus Putnam started planning a new settlement in the Ohio Valley at Marietta.

Ironic fortune of war: Fort Ticonderoga, where the Dorchester Heights armaments came from, was retaken a year later with an identical strategy and outcome: The British forces hauled cannons up a nearby mountain and aimed them at the fort. Like the British at Dorchester, the Americans realized their plight and abandoned the fort.

1 Henry Knox conceived and executed an expedition to recover armaments captured from the British from Fort Ticonderoga, then bring them to Boston to fortify the Dorchester Heights. He reached the fort on December 5, 1775 and departed with 8 brass mortars, 6 iron mortars, one howitzer, 13 brass cannon, 30 iron cannon, a barrel of flints, and 2,300 pounds of lead. Transporting this huge assemblage required 42 sleds, 80 teams of oxen. They had to navigate rivers, wait for ample snow and ice coverage, and drag them over the hill country of western Massachusetts. But they persevered. One historian called it the greatest logistical feat of the entire war.

Sources:

“March 4, 1776, Fortification of Dorchester Heights,” massmoments.org

Baker, David B., “Rufus Putnam the Early Years,” Early Marietta local history blog

Brooks, Noah, Henry Knox, Soldier of the Revolution

Buell, Rowena, Memoirs of Rufus Putnam

Fortification of Dorchester Heights, Wikipedia

“Fort Ticonderoga (1775),” battlefields.org

French, Allen, The Siege of Boston

Frothingham, Richard, History of the Siege of Boston etc.

Shallot, Todd, Structures in the Stream, Water, Science, and the Rise of the U. S. Army

The Writings of George Washington, Vol 3, 1775-76