John Miller was bound and left in camp by a Delaware Indian war party. The Delaware, with George Morgan White Eyes (“George”), were headed for Waterford to attack settlers at Fort Frye in March of 1791. John knew he had to escape and warn his friends at Waterford. He had lived with them in the summer of 1790, using his hunting skills to supply wild game for the fledgling settlement.

Miller was a “Stockbridge Indian” from Massachusetts who had come to Marietta in 1788 with General James Mitchell Varnum. He had lived most of his life among white people and was less attached to his native heritage. John and George were friends at Princeton University in the 1780’s. A chance meeting between the two in 1790 at Fort Harmar rekindled their friendship. George hired John as a guide and hunter. But after several months with him and his Delaware tribe at Sandusky, John longed to rejoin his friends at Waterford.

The war party headed to southeast Ohio from Sandusky. John Miller tagged along so he could return to the area, knowing he’d have to find a way out. They camped near present day Duncan Falls on the Muskingum River. It became clear they planned to attack soon. John had to think fast: how could he stay behind without raising suspicion? He deliberately cut his foot while chopping wood, pretending it was accidental. They left him in camp but tied him up, uncertain of his intentions.

Fort Frye, located just below present day Beverly, Ohio, was named for Lt. Joseph Frye who designed the structure which was erected after the massacre at Big Bottom in January, 1791. It was triangular, not a typical design for frontier blockhouse forts. Image from Samuel Hildreth’s Pioneer History.

John watched and listened after the Delaware war party left camp on that cold March morning. A few birds chirped in the mist; deer wandered through the camp. Otherwise it was still. Were they gone? Yes. He struggled to free himself. His mind was racing. How could he get to Waterford before the war party attacked? He watched the Muskingum River flow by, swollen by heavy rains. That was it! He would have to take his chances floating down the dangerously swift water. By late afternoon he was free. He scrambled to retrieve logs and grapevine to build a raft. At dusk he set off, his foot throbbing. Darkness enveloped him; now he was at the mercy of the river.

George Morgan White Eyes was the son of Delaware chief White Eyes. Early in the Revolutionary War, White Eyes had led efforts by the Delaware to build better relations with the Americans. George Morgan, Indian agent and advocate, helped arrange a treaty between the Delaware and Americans. The Delaware offered the Americans access across tribal lands and its “best and most expert warriors” in support of U.S. troops. The US pledged basic necessities (food and supplies), protection for non combatant Delaware people, and a territorial guarantee with potential future statehood.

It was fleeting vision of an idealistic future: Indians and whites living in peace with each other. But it wasn’t to be. The Delaware honored its promises; the United States did not. And Chief White Eyes was murdered in late 1778 while guiding U.S. Troops, severely straining the relationship. George was 8 years old at the time, facing an uncertain future.

At daybreak, John Miller was chilled through from a night on the water. He panicked as he spotted a camp fire. It was the war party. He jerked as rifle fire echoed in the hills. Fortunately, they were hunting and not firing at him. He clung prostrate to the raft, heart pounding, but skimmed past without being seen.

He landed just above Fort Frye and cautiously approached the fort. He was dressed like an Indian but spoke good English and named people in the fort who knew him. They let him in - at gun point. Some didn’t believe his warning and thought he was a spy for the Indians. Fortunately the commander, Captain William Gray, did believe him. John gave him full details of the Indians’ plan. The settlers at Fort Frye went on full alert, working feverishly to secure the fort. Indians did finally attack after a few days and were repulsed. Miller’s warning saved many lives.

John Miller was now in a difficult spot - like a man without a country. The Delaware Indians would torture and kill him if caught. And some of the white settlers distrusted him. He was dismayed by his predicament - and afraid. How could he be distrusted by the Indians and whites when he had friends in both groups? Yet so it was. John Miller fled to Marietta and returned to New England. His experiment at living in the Ohio Country was over.

George White Eyes’ life was also in cultural limbo. He and two other chiefs’ sons had been sent to Princeton, New Jersey in 1779 to be educated as a conciliatory gesture by Americans for his father White Eyes’ murder. The boys lived there under the guidance of George Morgan, George Morgan White Eyes namesake.

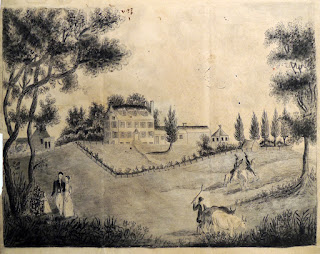

George Morgan’s Prospect Farm, ca 1797 where George Morgan White Eyes was housed. It was adjacent to College of New Jersey, as Princeton University was known at the time. From slavery.Princeton.edu.

George was overwhelmed at being thrust into an entirely new culture. He missed his father. Gone were the familiar people, landscape, and Delaware Indian customs. Yet he excelled in his classes at a private school, and then at The College of New Jersey. By his senior year, though, he had become disillusioned. And his mentor George Morgan was moving west to Missouri. He recommended to Congress that young George’s education be continued at Yale but received no response. In August 1789, George Morgan White Eyes wrote to George Washington, “I am very sorry that the Education you have given & views you must have had when you took me into your Possession, & the Friendship which my father had for the United States (which I suppose is the chief Cause) are not sufficient Inducements, to your further providing for me.” With ambivalent feelings, George returned in 1789 to his native Delaware Indians in Ohio.

Now he too was like a man without a country, restless, uncertain of his place. White culture was unsettling to him, and after a ten year absence, reentry into his former Delaware culture would be a challenge. He had missed years of indoctrination and training - in fighting, scouting, and survival skills. And would he be accepted by Indians who barely knew him or his father?

George apparently fit in with his tribe. He took a wife, described as very young with long dark hair. Sadly, his life devolved into random aimless wandering, with her and some of his Delaware companions. One historical note says that George inherited some assets from his father White Eyes but “….squandered his (inheritance) in debauchery.” Another historian described their daily routine as “hunting by day and drinking by night.” We get a glimpse into his life through two fascinating encounters with George White Eyes by prominent Ohioans.

Thomas Ewing, later a Lancaster attorney and U. S. Senator, had a chance meeting with him in 1796. Ewing was 6 years old, fishing on the Muskingum River with his father and older brother. Suddenly an Indian with a rifle appeared on a large rock and motioned them to shore. They complied, fearful on the Indian’s intentions. Fortunately, he only need help dragging a deer he had shot to the river. They loaded it into the canoe and proceeded with some trepidation to the Indians’ camp. One of the group was George White Eyes.

There was a feast of venison and ceremonial pipe smoking. Ewing’s father remembered that George had several of his school books in camp, including a “well thumbed” book of Eschylus Greek tragedies which he “took pride in exhibiting.” Ewing remembered the wife as “beautiful - dressed in a black silk robe…ornamented with silver brooches.” The next morning young Thomas recalled having fun playing with other Indian boys and learning how to more expertly gig fish.

Ephraim Cutler, prominent early settler and civic leader, was active in a work party that recovered salt from deposits near present day Chandlersville in southern Muskingum County. Salt was a valuable and scarce resource at the time. Groups from different settlements worked on a schedule. Indians often visited the site.

One night in 1796 there was a memorable episode involving George Morgan White Eyes. He, his wife, and a Stockbridge Indian named Old Tom were drinking. George and Old Tom started arguing; Tom struck George with the blunt end of a tomahawk and fled. His wife came running into the salt camp and begged for help. Cutler and others found George unconscious and barely breathing. They brought him to the salt works. Soon a large number of Indians gathered. Several squaws went to work. They built a fire, heated a large flat rock, poured water over the rock, and directed the steam vapor around George’s face and head. This went on for several hours. The next day he was awake, alert though probably hung over, and left with the hunting party.

Two years later George Morgan White Eyes was dead. He drunkenly threatened a young man who fatally shot him. George had never found peace, trapped in a no man’s land between his native heritage, white culture, and alcoholism. We have no record about John Miller’s life after he left Ohio. As an Indian living in white man’s society, he too was out of place in the Ohio Country. Such were the conflicts that many Native Americans experienced in the early years.

Thank for telling the story of the Indians who are part of our Valley's past. I knew some attended schools or lived in the eastern states, but did not realize the role George Washington and other had in providing those avenues. I don't want to use "opportunity" because it did not benefit George Morgan WHite Eyes or John Miller.

ReplyDeleteGeorge Washington didn’t get involved, as a rule. George Morgan White Eyes was a personal friends son, and the first recipient of financial aid.

ReplyDelete