I have often heard stories about the original Marietta Country Club ("MCC"). There are still traces of the facility along Chamberlain Drive in Devola where the course was located, along with other reminders, such as the street name "Country Club Drive." I learned in my research that there were two country clubs in Marietta in the late 1920's with fascinating histories.

S. Durward Hoag was original owner of the Lafayette Hotel, local historian, and civic booster (he was a prime mover in the successful effort to have Interstate 77 routed through Marietta). He was a member of the original club and recalled many details. The original MCC was formed in 1900 by local citizens including Col. John H. Mills, A. Dewey Follette, Fidelio Henry, C. Fred Moore, Charles A. Ludey, Frank Penrose, William T. Hastings. These men raised money to build a clubhouse, lease 24 acres from the Devol and Chamberlain farms, and build a 9-hole golf course.

The Marietta Register of March 21, 1901 effusively announced the construction of the clubhouse. News articles in those days about new improvements often sounded like advertising promotions of today. The headline proclaimed "The Marietta Country Club will have Most Delightful Quarters." Some of the narrative is reproduced below:

"The grounds are well arranged........an ideal spot for the indoor and outdoor sports to be carried on by the Club." The building would be "old Dutch Colonial style of architecture. With its wide verandas extending all 'round the building, mostly covered by a long sweeping shingle roof, the very thought of its shelter creates a pleasant anticipation of comfort to its members, during the warm summer days and evenings....On entering the building...you are ushered into the Great Hall,....which is the general living and reception room of the club." The dining room connected with the Great Hall would have a "commanding view of the beautiful Muskingum River and hills on the opposite side... Back of the Clubhouse will be located tennis courts and other outdoor games of a similar nature...The Golf Links...will occupy a very large area...This game (golf) is one of the most fascinating and is gaining national prominence in this as well other countries."

The author presciently noted that "The Club is in fine financial condition and will start off ...with no indebtedness...This is an important matter with all newly organized clubs." The membership was listed as 160 with more to follow. The article concluded that "the success of the Marietta Country Club is well assured." Can I get an amen?

The author presciently noted that "The Club is in fine financial condition and will start off ...with no indebtedness...This is an important matter with all newly organized clubs." The membership was listed as 160 with more to follow. The article concluded that "the success of the Marietta Country Club is well assured." Can I get an amen?

It seemed counter intuitive that a small rural town in the early 1900's would have enough affluent citizens to support such a club. But Marietta was prosperous then, probably more so than today. There were dozens of major industries thriving at the time. The Century Review Board of Trade edition published in 1900 listed more than two dozen manufacturing firms. Several enjoyed national reputations -such as the Marietta Chair Company, Stevens Organ, stove manufacturer A. T. Nye and Son, and Strecker Brothers leather goods. There were three brick yards. Oil and gas activity was intense. The Century Review reported that "Within fifty miles of Marietta there are 8,000 wells, giving forth above a million barrels per month."

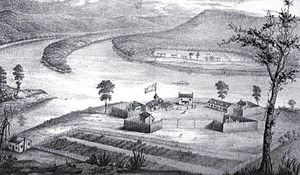

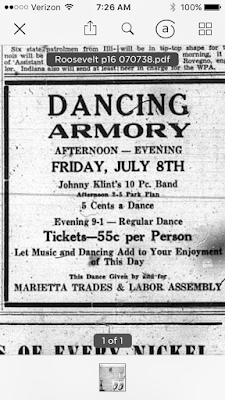

MCC became the social center of Marietta as members enjoyed the many activities at the club. The clubhouse was enlarged in 1908. Below are photos of that period, including an activity schedule in 1923.

Marietta Country Clubhouse. Photo from S. Durward Hoag Marietta Times article in 1974 shared by Julie Lambert on Marietta Memories Facebook page. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

Stag Night 1907

Photo with caption from S. Durward Hoag Marietta Times article in 1974 shared by Julie Lambert on Marietta Memories Facebook page. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

Scene at Marietta Country Club. Lew Peddinghaus was a jeweler whose business was bought by Baker & Baker Jewelers in 1918. Photo from S. Durward Hoag Marietta Times article in 1974 shared by Julie Lambert on Marietta Memories Facebook page. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

1923 activities schedule. Note the names of many prominent citizens of that time.

Copied from a booklet viewed at Washington County Public Library, Genealogy and Local History Library. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

There were lots of anecdotes about the old country club; one such was told by Mr. Hoag. It seems that there was a chicken coop on a neighboring farm located along the fairway of the third hole. One day Hoag caught one of the chickens and gave it to his caddy. Upon finishing the hole, he then carefully placed the chicken on the green laying down with its head folded under its wing. Doing that quieted the bird into hypnotic-like state. Your author researched this phenomenon and discovered that some chickens do sleep like this; and some can be hypnotized in other ways.

Playing behind Hoag were three of his friends, Attorney Tom Summers, Eddie Williams, and Will. V. Hayes. They approached the green and noticed the "lifeless" chicken. Hayes gingerly jostled the chicken with his putter. They were startled as it sprang to life and scampered cackling off the green. Back in the locker room the three could convince no one that they had found a chicken "sleeping" on the green.

By the early 1920's, a separate group within MCC wanted a 18 hole golf course. That group formed the Washington Country Club ("WCC"), purchased land where the current Marietta Country Club is located on Pike Street, and installed an 18 hole golf course. The article below trumpeted the construction of the clubhouse for the new club.

Image of Marietta Times front page announcing Washington Country Clubhouse construction, courtesy Local History and Genealogy Department of Washington County Public Library. CLICK TO ENLARGE.

But it seemed unlikely that Marietta could support two country clubs. Both clubs had fewer members to support their respective operations than the former combined group. WCC sold one hundred $1,000 memberships but still needed multiple mortgage and bank loans for the construction. And in the early 1930's the depression put the economy in a tailspin, straining both clubs financially.

On June 11, 1933, the MCC clubhouse burned to the ground. The fire was discovered at 6:15 p.m. on a Sunday in the men's locker room. Golfers had finished in the locker room, so did not notice the fire until it had a full start. Quick action by members, employees, and neighbors saved some furnishings and equipment. Insurance paid out $10,900, likely covering most of the loss. The club continued operating for another year without a club house.

Early in 1934, WCC's heavy debt and declining revenues forced it into bankruptcy. The property was offered for sale by the Union Joint Stock Land Bank of Detroit for $12,500. MCC purchased the WCC property. Once again the two country clubs were together as the Marietta Country Club which survives today.

The former MCC land leased from the Chamberlain and Devol farms was immediately returned to farming. Soon cabbage, corn, and tomatoes grew where a short time ago Marietta's elite had gathered for golfing and the country club life.

MCC activities calendar for June, 1955. There were lots of activities: bridge, stag night, golf, club party. Photo by author of calendar located at Local History and Genealogy Department of Washington County Public Library.

CLICK TO ENLARGE.

Today Marietta Country Club continues but with reduced membership from the peak years of 10-20 years ago. This is in line with national trends of declining club membership and interest in golf, long the staple activity of country clubs. These trends are attributed to changing demographics, lifestyles, and family priorities.

But MCC has persevered and survived for more than a century, through the determination of its members and staff. Clubs like MCC must hustle to attract members with new activities, proactive marketing, and flexible financing options. Who knows, maybe country clubs can help wean our population from their electronic devices by enjoying healthy activities and interacting directly with other human beings. What a concept. It can be fun. Keep on keepin' on, MCC.

But MCC has persevered and survived for more than a century, through the determination of its members and staff. Clubs like MCC must hustle to attract members with new activities, proactive marketing, and flexible financing options. Who knows, maybe country clubs can help wean our population from their electronic devices by enjoying healthy activities and interacting directly with other human beings. What a concept. It can be fun. Keep on keepin' on, MCC.