Perhaps you've heard of the so-called "Celeron Plates." Or, maybe not. It's not headline material for most of us. But it has been endlessly fascinating for history scholars.

Pierre Joseph Celeron De Blainville*, a French military leader, led an expedition down the Ohio River Valley in 1749. The expedition buried lead plates at major tributaries, including the Muskingum River, to establish French claim to land in the Ohio River Valley. It was a curious enterprise built on the dubious premise that burying plates could establish a land claim. Who was this Celeron guy and why were they burying lead plates? First, some background.

The French and English were vying for control of America’s interior lands in the mid 1700's. The French pursued their claim to Ohio Valley lands based on earlier explorations by LaSalle in 1669 and 1682. The British had other ideas. They fought King George’s War from 1743-1748. The British were able to disrupt the French fur trade and undermine French influence with Native Americans in the upper Ohio River Valley. Also, Virginia colonists set up The Ohio Land Company (unrelated to the Ohio Company of Associates which later settled Marietta) intended to acquire land in the upper Ohio Valley.

CLICK TO ENLARGE. Map of colonial interests in 1750. New France was the blue area, British in red, Spanish brown. The border of red and blue lands in western PA and the upper Ohio Valley were being contested.

British inroads jolted the French into action. The governor of Canada commissioned Pierre Joseph Celeron De Blainville (“Celeron”) to lead an expedition down the Ohio Valley in 1749. Its purpose was to reassert French claims in the area, renew friendship with Indians, and chase out British traders.

Celeron was a French Canadian soldier born December 29, 1693, in Montreal. His father Jean-Baptiste Celeron was granted a lordship over Blainville, which accounts for the suffix “de Blainville.” Celeron became a cadet in the French colonial army at age 13. He was commissioned as ensign at age 20 and was a nearly a 40 year veteran when he began the Ohio River expedition. Celeron was selected in part for his “cool but tough” attitude towards the Indians in previous commands.

The expedition began near Montreal, Canada on June 15, 1749. It was an eclectic group, about 250 strong. There were French soldiers, Canadian militia, and a few dozen Indians. Randall and Ryan’s History of Ohio Volume I offers a colorful imagined description: “The flotilla ....formed a bizarre but picturesque outfit, the French soldiers and Canadians, in their gay costumes and semi-medieval armour, the half naked, copper-skinned savages (Indians) with their barbarian weapons, the flying banners of France, all crowded in frail white birch canoes, that floated on the blue waters of the river like tiny paper shells; it must have seemed like a tableau vivant (a static, posed group of actors) rather than an army...”

CLICK TO ENLARGE. Map of the route followed by Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville along the Ohio River in 1749, drawn by Father Joseph Pierre de Bonnecamps, viewed at Wikipedia.com.

A priest, Father Jean Pierre de Bonnechamps, was chaplain and also the dutiful navigator for the expedition. He used a sextant, drew maps, and made notes on the expedition. Their Indian diplomat/envoy was Phillips Thomas Joncaire, a French officer of Seneca Indian ancestry. He was often sent ahead to assuage Indians, who were predictably alarmed by such a large force of mostly white men.

It was a strenuous journey at the start for the expedition’s canoe flotilla. They had to paddle the length of Lake Ontario, portage around Niagara Falls, paddle further on Lake Erie, and portage again to Lake Chautauqua. A portage - moving men, canoes, and supplies across dry land to the next waterway - is an exhausting and time consuming task. From there they followed Conewango Creek to the Allegheny River and eventually to the Ohio River.

Their primary mission was to bury lead plates designating French land claims. They did this at major tributaries of the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers. Each plate burial was accompanied by a ceremony. Soldiers lined up in formation. King Louis XV was proclaimed lord of that region. There were songs, cheers, and musket volleys fired. A tin plate erected on a tree gave notice of each buried plate which was placed near that tree.

CLICK TO ENLARGE.

12 x 20 foot mural at the Wheeling Civic Center - “French exploration of the Ohio Valley,” by Mark Missman. This painting illustrates the ceremony that accompanied the burial of each lead plate. The mural was designed to commemorate the presence of the French explorers and their Jesuit companions in the Upper Ohio Valley. One of the lead plates was buried at the confluence of the Ohio River and Wheeling Creek.

The burying of plates seems today like a curious way to make a land claim. This technique was a common method used in medieval Europe for land claims. But realistically, who would ever see them - after all, they were buried? And if the plates were found, their purpose and validity would surely be questioned. But the French were committed their mission.

One of the plates was buried at the mouth of the Muskingum River on August 15, 1749. A metal sign was posted on a tree to mark the location of the buried plate. The narrative on the sign was very formal; brevity was not part of the French communication style:

The 15th of August, 1749, we, Celoron, Knight of the Royal and Military Order of St. Louis, Captain commanding a detachment sent by the orders of Monsieur the Marquis de la Galissoniere, Governor-General of Canada, upon the Beautiful River, otherwise called the River Oyo, accompanied by the principal officers of our detachment, have buried at the foot of a maple tree, which forms a triangle with a red oak and an elm tree, at the entrance of the river Jenuanguekouan (Muskingum), at the western bank of that river, a leaden plate, and have attached to a tree on the same spot, the arms of the King. In testimony whereof we have drawn up and signed the present official statement, along with the Messrs. the officers at our camp, the 15th of August, 1749.

In 1798 a flood had washed away part of the Muskingum River bank, exposing the plate. It was discovered by boys swimming there. Not realizing its importance, they melted much of the lead plate for musket balls. Paul Fearing became aware of it. William Woodbridge, then of Marietta, had recently been to Gallipolis and knew some French. He was able to decipher enough of the plate to realize that it was deposited by the French as a land claim. The probable inscription, reconstructed based on other plates, is given below:

In the year 1749, in the reign of Louis the XV, King of France, we Celoron, commander of the detachment sent by the Marquis de la Galissoniere, Governor-General of New France, to reestablish peace in some villages of these Cantons, have buried this plate at the confluence of the Ohio and the river Yenanguekouan (Muskingum), the 15th of August, for a monument of the renewal of possession which we have taken of the said river Ohio, and of all those which fall into it, and of all the territories on both sides as far as the source of the said rivers, as the preceding Kings of France have possessed or should possess them, and as they are maintained therein by arms and by treaties, and especially by those of Riswick, Utrecht and of Aix la Chapelle

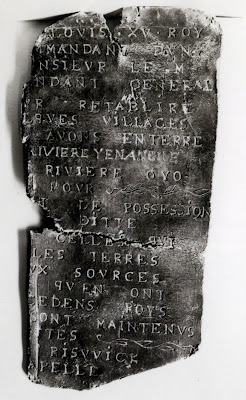

CLICK TO ENLARGE.

Image of the Celeron plate buried at the Muskingum River. Over half of the original plate was destroyed to make musket balls. From the American Antiquarian Society where the plate resides. About halfway down, note the word “Yenangue”, part of the hyphenated Yenanguekouan, an early Indian name for Muskingum. In the next line down, see “Rivière Oyo,” French for Ohio River.

The wording on the plates was somewhat confusing to historians and not always consistent. Charles B. Galbreath, an editor of the journal kept by Celeron, wryly observed that "The artist (who engraved the plates), Paul De Brosse, like Celeron himself, had evidently not taken first prize in spelling words of his native tongue and was somewhat careless..." Another author noted that “the French (wording) is none of the purest and the accents, apostrophes, and punctuation are wanting...”

Celeron’s expedition also sought to placate the region’s Indians and remove British traders. Neither goal was realistic and ultimately failed. On August 6, at the Indian village called Logstown northwest of Pittsburgh, Celeron found six English colonial traders present with large bundles of furs bound for Philadelphia. He ordered them out of the area and wrote a note to Governor Hamilton of Pennsylvania asking that he keep traders from trespassing on French land. Other British traders near Indian villages at the mouth of the Scioto River were asked to leave. Those requests and other actions to dislodge the British were largely ignored.

The expedition held numerous discussions with tribes in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Each exchange had an elaborate protocol, typical of communication between Indians and whites in that time period. A speech by one party was preceded by a gift of wampum belts to convey the importance, sincerity, or urgency of the topic. A similar speech was made when the other party responded, often on the day following.

CLICK TO ENLARGE.

Robert Griffing painting of imagined expedition stop near Logstown in western Pennsylvania. Notice Indians present; there were Iroquois Indians in the expedition. The large tree was a cottonwood tree. From the diary of Father Joseph Pierre Bonnecamp: “We dined in a hollow cottonwood tree in which twenty-nine men could be ranged side by side.”

Language used was flattering, deferential, and endlessly courteous, though often insincere. The speeches followed a common pattern. Celeron alternately scolded and cajoled the Indians to reject the British and embrace the French. The Indians usually demurred, sometimes feigned compliance, occasionally disagreed with him.

Celeron invested hours and hours in communicating with the Indians - listening, composing speeches, enduring tedious ceremonies - mostly for naught. The Indians viewed Celeron’s intentions with contempt. They were too closely tied in with the British who offered them cheaper goods, trusted friendship, and rum - which Indians thought offered a quicker high than the whiskey supplied by the French.

The expedition continued down the Ohio River to the Great Miami, then northward to Lake Erie and eventually back to Montreal. Celeron Pierre Joseph DeBlainville was awarded a command in Detroit. The French and British continued as adversaries. The French and Indian War (1756-1763) eventually resolved the issue in favor of the British. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 awarded land from the Mississippi River east to the Appalachian mountains (which included the Ohio Valley) area to the British.

One of the expedition’s lead plates was buried at the Kanawha River near present day Point Pleasant WV. A boy discovered that plate in 1846, a curious reminder of the futile French claim made nearly 100 years earlier.

*His name also appears as “Celoron” and the title part of his name as “De Bienville.”

SOURCES:

SOURCES:

Bumgardner, Stan, “Celeron de Blainville,” wvencyclopedia.org

Biography – CÉLORON DE BLAINVILLE, PIERRE-JOSEPH – Volume III (1741-1770) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography, viewed at http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/celoron_de_blainville_pierre_joseph_3E.html

Galbreath, C. B., Expedition of Celeron to the Ohio Country in 1749, Columbus, Ohio, F. J. Herr Publishing Company, 1921

Hulbert, Archer Butler, The Ohio River, a Course of Empire, New York, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1906

Howe, Henry, Historical Collections of Ohio, an Encyclopedia of the State, Volume 2, 1907

Ohio History Journal Vol 29, “Celeron’s Journal, edited by A. A. Lambing” and

"Account of the Voyage on the Beautiful River in 1749 Under the Direction of Monsieur de Celeron, by Father Bonnecamps.”

Vanderwerth, W. C., and Carmack, William R., Indian Oratory, Famous Speeches by Noted Indian Chiefs, University of Oklahoma Press, 1979.