It must have been a startling sight: 200 Indians marching towards Fort Harmar in December of 1788 with an American flag. There was musket fire - a friendly salute from the Indians, followed by several minutes of a cannon and musket fire salute from Fort Harmar. The troops escorted the Indians into the fort with music playing. So began treaty negotiations at Fort Harmar. The few dozen settlers of the fledgling Marietta community were on edge.

This topic came up recently when Bill Reynolds, Historian at Campus Martius Museum in Marietta, showed me the undated photo below. The sign claims that the Treaty of Fort Harmar was signed in this building. Could this have been the original "council house" (a meeting place for Indians) built for

the treaty negotiations?

the treaty negotiations?

Sign says: Log House in which Gov. St. Clair signed Treaty with Indians 1788. The photo is undated; location uncertain; probably somewhere in Harmar village. Photo courtesy of Bill Reynolds.

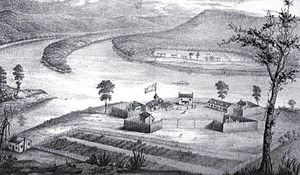

In this early drawing of Fort Harmar, the council house appears at the bottom left.

Source: Wikipedia:

This photo triggered my interest in the council house. I have pored over historical texts, journals, and letters. But I have found nothing yet mentioning its construction or when it was built.

Maybe it doesn't matter. The council house symbolizes a year-long drama on the early Ohio frontier culminating in the Treaty of Fort Harmar. Here are some of the issues and highlights of the story.

The issues and timeline

Late 1780's: There were long standing tensions between Indians and white settlers:

- Indians sought guaranteed lands, protection against harassment, and equality with whites.

- Settlers wanted land, room to expand, and freedom from raids.

- The U. S. Government wanted peace and the ability to sell "Indianless" land to white settlers for expansion - and to reduce government debt.

A treaty seemed like the most practical solution to bring lasting peace. The Indians were first to express an interest in a broad treaty.

November/December, 1786: Multiple Indian tribes held a council at Brownstown, near Detroit. They sought to form a united confederation to negotiate with the Americans. Charismatic Mohawk chief Joseph Brant advised his peers that "the interests of any one nation should be the welfare of all others." The Indians asserted that the United States should consider Indians as equals and negotiate treaties with the entire confederation rather than separate tribes. After the council, Brant wrote a letter to Congress requesting negotiations.

Portrait of Chief Joseph Brant from wikipedia.com

July 13, 1787: The Ordinance of 1787 created the Northwest Territory, the first U.S. territory outside the original 13 states. The Ordinance had language foreshadowing the Bill of Rights for its citizens: trial by jury, prohibition of slavery, religious freedom, encouragement of education, and more. There was also effusive language calling for the civilized treatment of Indians. But there were no rights given Indians nor territory set aside for them.

October 22, 1787: Congress directed Arthur St. Clair, the Governor of the newly established Northwest Territory, to pursue a general treaty with all of the tribes. "The objects of such a treaty are, the removing all causes of controversy, regulating trade, and settling boundaries." It was quite a responsibility to be thrust upon the new governor of a new territory.

October 27, 1787: Congress agreed to sell 1,500,000 acres of land in the new territory to The Ohio Company for settlement. This and other land sales would bring a major influx of white settlers into areas that Indians considered their own.

January 27, 1788. St. Clair responded to the Congressional directive in a letter to Secretary of War Henry Knox. He recommended a treaty, though he doubted that it would resolve the conflicts. A date for a treaty meeting was set for May 1, 1788 at the Falls of the Muskingum River - about 70 miles north of Fort Harmar. Invitations were sent to Indian tribes.

Preparing for the treaty gathering was a major logistical effort. Congress set aside $20,000 ($540,000 in today's dollars) for "goods" needed. Goods included supplies to build a council house, huts for temporary lodging, food, equipment, and gifts as "incentives" (bribes, some said) for Indian cooperation.

March 1788. St. Clair writes to the United States Treasury Board, frustrated at the refusal of the State of Pennsylvania to honor a warrant for $1,000 to help pay for treaty supplies. The U.S. Treasury had no money; states were asked to provide funds when needed. Sometimes they didn't. St Clair admonishes the Board to find the money some other way, stating emphatically that "the money is absolutely necessary" to complete the treaty.

March 9, 1788. Some treaty supplies had to be transported by boat from an outpost at the Falls of the Ohio (near Louisville KY). Ensign Spear was assigned this task, along with a complement of "one serg't, one corp'l, and 16 privates." As they approached the Falls of Ohio, Indians attacked them. Two of the soldiers were killed, and they retreated down the river 18 miles. They built a temporary blockhouse as a defense and sent a friendly trapper as a messenger requesting help from Major John Wyllys at the Falls outpost.

No help arrived. Several days later their provisions ran out. Fortunately, by chance, they met a supply boat headed downriver which was able to resupply them. They continued to the Falls of the Ohio, loaded the provisions, and returned upriver to Fort Harmar. Imagine rowing a loaded keelboat - powered only by oars or poles - upriver against the current for 400+ miles. They arrived back at Fort Harmar in late April, nearly seven weeks after they left.

Spring 1788: The Indians were not ready for a treaty meeting in May. There was internal dissention. Wyandots wanted a separate treaty with Americans. Delawares, Potowatomies, and Hurons wanted a set boundary line. Shawnees and Miamis wanted no land give-up and opposed negotiations with Americans. A council meeting near Sandusky was planned to resolve their differences. But the date was uncertain.

June 13. The treaty gathering at last seemed imminent. General Josiah Harmar dispatched Lt. McDowell and 22 soldiers with the treaty provisions from Fort Harmar to the Falls of the Muskingum (near present day Duncan Falls, Ohio). The party included a sub-sergeant, corporal, and 20 privates. The group began work building a council house and huts for the treaty attendees. Meanwhile a large group of Indians gathered there for the anticipated meetings.

July 12. Unexpected trouble. Some Indians raided the treaty supplies, apparently trying to steal some of the contents. The raid was repulsed, though with the loss of two soldiers killed, others wounded. One Indian was killed, another wounded. The dead Indian was found to be a Chippewa. The next morning Delawares, disclaiming any involvement in the raid, brought in six Chippewas accused of being in the raiding party. They were taken prisoner. A servant of Major Duncan, an Indian trader and future namesake of the Falls treaty location, also died in the attack.

July 14. St. Clair's reaction to the raid was immediate. He cancelled the meeting. In a letter to Secretary of War Knox, he stated that "After such an insult, to meet the Indians at that place,...I thought inconsistent with the dignity of the United States." He ordered troops from Fort Harmar to retrieve Lt. McDowell's party and the provisions at the Falls. He sent a stern, derisive message demanding an apology to the Indians who were holding a council at Detroit. It effectively blamed the Indian tribes for the raid, though it seemed more likely that the perpetrators were a few Indians acting on their own. The St. Clair letter was taken by the Shawnees and Miamis as a clear signal that Americans would not negotiate in good faith. They increased their attacks against soldiers and settlers in Ohio country.

July 20. The Indian prisoners from the raid arrived at Fort Harmar. A few days later, two of them escaped as they were being escorted to the "necessary" (Major Ebenezer Denny's term for outhouse) outside the Fort. Four soldiers guarded the group as they walked past a corn patch. The Indians had figured out that their shackles could be slipped off. Two of them waited for the right moment, slipped off the shackles, disappeared into the corn. The guards were flogged, though ill fitting shackles were likely not their fault.

Early August. The Indians held a council at the Falls but could not reach agreement on a response to St. Clair. Delaware Chief Captain Pipe visited St. Clair seeking the release of the Chippewa prisoners, claiming that Ottawas were the real culprits. St. Clair said no way. Captain Pipe was an effective diplomat: He had conferred with General Harmar on several occasions, visited Fort Pitt, greeted the settlers at Marietta on their arrival, traded with the Fort Harmar Indian contractor, and dined at the home of Rufus Putnam. He then countered with an offer to take a single prisoner with him to Detroit to counter the inflammatory statements of the escapees. St. Clair thought that was a good idea and accepted the offer.

September 9. Seneca Chiefs Cornplanter and Halftown, along with 51 other Indians, arrived at Fort Harmar for the treaty. Historian H. Z. Williams describes Cornplanter as a "civilized savage" who was friendly to US and tried to promote good will on both sides. The Ohio Company later awarded him some land because of his efforts to promote harmony.

Portrait of Cornplanter from wikipedia.com

Mid September. St. Clair received a message saying that "a large body of Indians may be expected here (for the treaty)," and they will be armed. He worried about a possible attack. Even if extra troops were available, it would be too little, too late, from too far away. He thought war with the western tribes (who would likely skip the treaty talks) was inevitable and even suggested a preemptive military strike to Secretary of War Knox.

October 20. Major Denny heard of rumors being circulated to discourage Indians from attending the treaty talks. One such rumor was that the whiskey intended for the Indians was poisoned and that blankets were infected with smallpox.

November 7. A delegation of Six Nations tribes arrived unexpectedly at Fort Harmar. Chief Captain David presented a friendly message authored by Joseph Brant - who was on his way to Fort Harmar - to St. Clair. The Indian confederation offered territorial concessions and requested that the treaty meetings be reconvened at Falls of the Muskingum. St Clair refused, stating that he would negotiate only at Fort Harmar where there was protection from possible Indian attacks. This was a stinging reference to the July attack at the Falls of the Muskingum. Brant was angered and turned back. He was suspected of influencing Shawnees, Miamis, and others to also boycott the treaty meetings. Realization that the United States would not even consider Indian proposals alienated many tribes. It became apparent that a truly comprehensive treaty agreement would be impossible.

December 13. Finally - a large group of Indians arrived to the pomp described above. But it was far from a representative group of all tribes. St. Clair wrote to Secretary of Foreign Affairs John Jay that the treaty would begin soon but "would....not be a very general meeting," since many tribes would not attend.

Day to day proceedings, mostly from Major Ebenezer Denny's journal:

December 14. Indian leaders, Governor Arthur St. Clair, Indian Commissioner General Richard Butler, and officers at Fort Harmar met in the Council House just outside Fort Harmar. The symbolic "council fire" was kindled there. John Heckewelder, a Moravian missionary who had lived among the Delaware and Tuscarawas, acted as a facilitator during the talks.

Deember 15-20. Extremely cold weather; river jammed with ice. Frequent meetings in the council house.

December 29. Wyandot Chief Shandotto gave a long speech on behalf of the Indians. He spoke of past betrayals by the Americans and asserted that the Ohio River must stand as the boundary for Indian lands. Governor St. Clair said that was impossible. There could be no deviation from previous treaty agreements.

December 30-January 5, 1789. No treaty meetings. Indians met among themselves.

January 5. Secretary Knox pressed St. Clair to pursue the treaty agreement. "I am persuaded that every thing will be done on your part that can be with propriety to avoid a war, and if that event should be inevitable, the evils of it can be justly charged to the Indians." In other words, war could be blamed on the Indians and provide an excuse to use force against them.

January 6. Governor St. Clair gave an accusatory and intimidating speech to the Indians. He explained how the defeat of the British (with whom the Indians sided) effectively ceded Indian lands to the United States. He said that America wanted peace but "if the Indians wanted war, they would have war." He proposed renewing the previous treaty at Fort McIntosh and with a provision allowing Indians the right to hunt anywhere in American territory. He also offered gifts of money and merchandise (the "incentives" for Indian cooperation).

January 9. The Indians capitulated and accepted the terms. They no other option. There were also other provisions, including prohibitions of white settlement in Indian territories and opening of trade with certain tribes.

January 12. The treaty was agreed to and signed. Denny noted cynically: "This was the last act of the farce; the articles (treaty) were signed." Technically there were two treaties with slightly different provisions for certain tribes.

A few days later, the main chiefs were given a celebration feast at Campus Martius, the fortified residential enclosure at Marietta. The Indians then departed.

The Legacy of the Treaty of Fort Harmar:

Marietta residents were grateful for the peace promised by the treaty and forwarded a letter of congratulations to Governor St. Clair for his effort. But success short lived. Indian hostilities soon broke out and continued for several years, ended finally by the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

Denny's assessment that the treaty was "a farce" was harsh but not far from the truth. Historians agree that despite good intentions the treaty resolved nothing new for some of these reasons:

- Most of the treaty language was a restatement of earlier treaties.

- Many tribes were absent and did not accept the treaty as valid. Some cited an earlier 1788 Indian council decision that no agreement would be valid unless all tribes agreed.

- Others said that their representatives who signed the treaty were not authorized to act for the tribe.

- As with earlier treaties, some claimed they did not understand what they signed. A Chippewa who signed at Fort Harmar later said that interpreters did not adequately explain the provisions.

There was a council house at Fort Harmar. But like the treaty and the Fort itself, it is largely lost in time. But I still want to find out what happened to it.

Sources:

Bond, Beverley Bond Jr, The Foundations of Ohio, A History of the State of Ohio Volume 1, Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio, 1941, pages 312-16 viewed at https://archive.org/stream/historyofstateof01witt#page/n9/mode/2up

"A Description of Fort Harmar" (author not identified), The National Magazine, A Monthly Journal of American History, Volume 1, page 26-31, viewed 9/29/2016 at https://books.google.com/books?id=y0RIAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Hurt, R. Douglas. The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720-1830. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996., pages 101-104

Military Journal of Major Ebenezer Denny, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, J. J. Lippincott and Company, 1859, pages 109+, accessed 9/29/16 at https://archive.org/stream/militaryjournalo00denn#page/n11/mode/2up

O'Donnell, James H., Ohio's First Peoples, Athens OH, Ohio University Press, 2004, pages 74-84

Outpost on the Wabash, 1787-1791. Edited by Gayle Thornbrough. Indiana Historical Society Publications, Volume 19. (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1957., pages 32-147

The St. Clair Papers, The Life and Public Services of Arthur St. Clair, William Henry Smith, editor, Cincinnati, Robert Clarke and Co., 1882, pages 36-104, viewed 9/29/2016 at https://archive.org/details/stclairpaperslif02smituoft

Treaty of Fort Harmar (1789), Ohio History Central, http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Treaty_of_Fort_Harmar_(1789), accessed 9/29/16

Williams, H. Z., History of Washington County Ohio, H. Z. Williams and Bro., Cleveland OH, 1881, pages 59-62, accessed 9/29/16 at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.20284997;view=1up;seq=7